NOTES BY A CIVIL ENGINEER

IN

EUROPE AND AMERICA

from 1838 to 1888

W.H. Lloyd

London

Baines and Scarsbrook, Printers,

Fairfax Road, N.W.

1900

INTRODUCTION.

Having been frequently asked by those closely connected with me to give some particulars of my Professional Wanderings, the following has been written in compliance with such desire.

Wanderings which, with some 130,000 miles of Atlantic and Pacific voyages—equivalent to about five times around the globe—besides many thousands of land journeys in parts but little known, cannot be altogether devoid of interest even in these days of cheap excursions everywhere; so that my experiences in France, Italy, Chili, Peru, the Argentine Provinces, Brazil, Central America, Guatemala, Mexico, the United States, Canada, and the West Indies, should, perhaps, yield some items of amusement, if not of instruction, and repay for the perusal of these rough notes of one of the earliest of Railway Engineers.

A RAILWAY PIONEER.

1838.

I VENTURE to consider that it was an evidence of my beloved father's sagacity and affectionate kindness when he determined that I should be articled to a civil engineer, for I am persuaded no other profession would have suited me so perfectly or have afforded me more pleasure, excitement, or novelty during the half-century, more or less, that I have had the honour to practise it.

At the time when this momentous decision was arrived at, I had scarcely reached sixteen years of age, but was considered to have completed my education ; but it soon became obvious to me that I had everything to learn, and that I was only approaching the threshold of the vast storehouse of practical information wherein, by my researches, my future would be either conducted to success or requited by failure.

On leaving my last school—that of the Rev. R. Simpson, at Islington, a worthy Scotch Presbyterian, with whom I had taken some interest in chemistry under Professor Ritchie of the London University, and had made some progress in drawing with the Dominie's nephew—I was first sent to a mechanical engineer's works beside the Thames, near the old timber bridge at Battersea, where the above bridge steamboats, the Bachelor, Bridegroom, Bride, and others were put in proper trim and arrayed in festive-coloured attire for

service. These works were nearly three miles from our residence at Stockwell, and one had to reach them by six a.m. across the meadows now forming the Battersea Park, and across the South-Western Railway, then in course of construction.

This experience was not agreeable, and I was soon transferred to some other works at Pimlico, where small steam vessels were constructed, and where I spent some time in the drawing-office, which suited me better; but just before my sixteenth birthday my father obtained an introduction to Mr. Joseph Gibbs, the civil engineer, through, I believe, a brother of the celebrated Arctic voyager. Sir James Back. Mr. Gibbs was then engaged in converting the Croydon canal into a railway, and, on being applied to, consented to take me as a pupil; and on the 15th October, 1838, I became articled to him for a term of four years, during which period it was stipulated I was to receive " such instruction as shall be most conducive to his " (the said pupil's) " advancement in the said Art and Profession, and all and every matters and thinfrs incidental thereto.^' And I have often thought that to have fulfilled such an obligation, on account of the innumerable ramifications of civil engineering, four hundred years of pupilage, instead of four, would scarcely have sufficed.

But under the tuition of my excellent and talented master I could not fail to acquire knowledge, and to become interested in the work being designed and executed by those with whom I was associated, who were universally men of refinement and of rare abilities; for at Gibbs's we did everything in the office. Our chief was an universal genius, a clever artist, a good architect, a most skilful mechanician, and not unskilful as a chemist; and as an evidence of such qualifications, I need only refer to pictures of his hung at the Royal Academy; to

PUPILAGE. r

his design for the Royal Exchange, to which the present structure bears an almost " Pecksniffian " resemblance ; to his bold and masterly plan for the drainage of Haartem Mere; and to his researches into the galvanization of metals, pursued in a laboratory behind our office.

The iriends of Gibbs were men of mark at the time t Lumley, the lessee of the Italian Opera; George Cruik-shank, the caricaturist; Edward Duncan, the water-colourist; Huggins, the marine painter to William the Fourth; and many others of like prominence; and, finally^ he was a man of great simplicity and of an amiable and generous disposition.

Our office was one of two houses standing in Kenning-ton Oval, opposite to what is now the entrance to the Surrey Cricket Ground, but which was then a market garden. In the adjoining house Mr. Gibbs lived with his family, and this made it very pleasant for me. Altogether the situation left little to be desired in any respect.

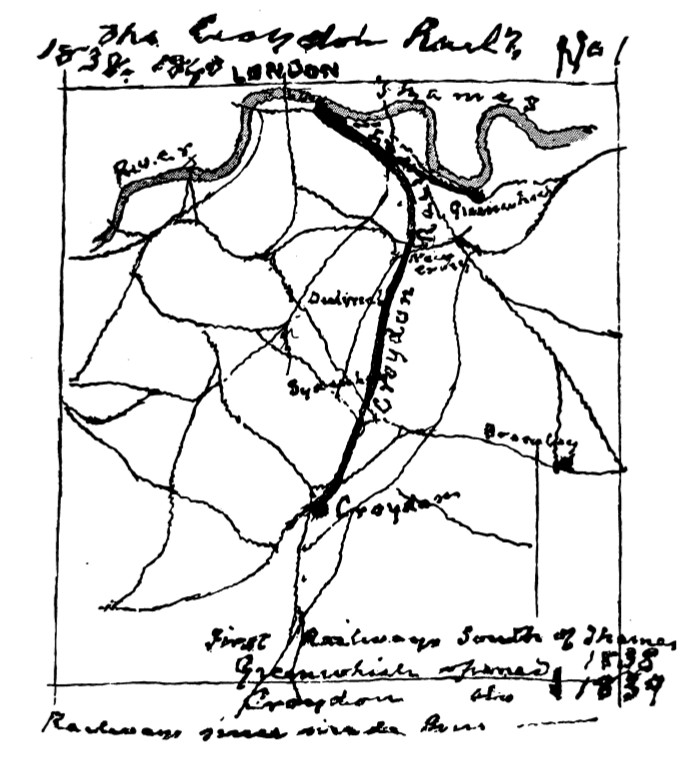

On my joining the profession of civil engineers in 1838, railways were quite in their infancy; the Greenwich line, the only one south of the Thames, had been in operation for a year or so, and the only line out of the metropolis north of the Thames—the London and Birmingham—had only then been just completed. The third line out of London was therefore the Croydon line, and this was not opened until the autumn of 1839, ^^^ became eventually the parent stock from which sprung both the South-Eastern and Brighton systems of communication, the Acts for which were under consideration by Parliament, and as yet unauthorized. Thus in 1839, within a radius of ten miles from London Bridge, there existed about fifteen miles of railway where, fifty years subsequently, nearer 150 miles of line were in use by the public. (See map No. i.)

The execution of the Croydon railway afforded me

S A RAILWAY PIONEER.

much valuable instruction, as there was not only originality in its design, but also considerable boldness in its execution. It was the first time, I believe, on which an incline of i in loo (52ft. per mile) was adopted, and upon which longitudinal sleepers were used. The construction of some of the bridges presented features of novelty, but these, to provide for subsequent widening of the line, have mostly disappeared. The acclivity of 52 feet per mile was considered by many at the time a very hazardous experiment, but, as will appear hereafter, inclines of four and even five times as steep are employed in later times.

The Croydon railway commenced at the present Lrondon Bridge Station, and ran parallel with the Greenwich line for about 2J miles; it then diverged towards New Cross, beyond which place the ascent of 52 feet per mile was rendered necessary to attain to the summit of Forest Hill, reached by the old canal by a long series of locks, and to accomplish this one of the deepest excavations then attempted became necessary, its depth being go feet in that most treacherous material, London clay. And here it was remarkable to unearth, thirty yards below the surface of the ground, and above ten yards above the level of the Thames, a bed of oyster shells a foot in thickness, retaining their shape until exposed.

Some fragments of the old Croydon Canal which were not utilized by the railway long remained, and on one of these I was sent to make drawings of a gas engine which had served to supply the canal with water. Of this I made careful drawings before its demolition, for it was then probably unique, though now gas engines are common enough, but perhaps not of a like simplicity; for it simply consisted of a tall upright cylinder standing in a well, and having a loose cover. Into the interior of this cylinder gas was introduced, and when it was charged the gas was exploded, and the vacuum thus

^

produced thereby drew up the water from below, to be then discharged into the canal.

At that time the vicinity of the railway was " truly rural/' and in great part was innocent of houses or population—Forest Hill, Sydenham, Norwood, were names of districts, and the stations were entitled the *'Dartmouth Arms" or the "Jolly Sailor" Stations, local hostelries in their vicinity which possibly still exist. The Crystal Palace did not rise above Sydenham until about twenty years after, and Norwood, with its Beulah Spa waters (as beneficial as many now obtained from abroad), was the favourite haunt of gipsies. But now my first love, the Croydon line, has been attacked on all sides, swallowed up and absorbed by monster extensions, and is scarcely to be now identified as the germ from which a mighty system of communication has sprung.

It was indeed a proud and happy day for me when, in the autumn of 1839, ^ secured an invitation for my beloved father to attend the opening of this my first railway, and to assist at the banquet customary on such occasions, at the terminus at Croydon, two years before his lamented death; and although I have, on many occasions since, attended not a few of such celebrations, none I am sure ever gratified me so much.

But the Croydon was not the only railway we had to do with, for Mr. Gibbs laid before Parliament plans for a line to Brighton, for which Edward Duncan supplied some large and beautiful views. He also submitted the project of a London and York line, so that in the production of such plans I had some minor share in surveys in the field, meeting at times with no little opposition from the owners of the land we were compelled to pass over, who stubbornly refused to admit of the benefits we desired to provide. At times men would

i

confront us with pitchforks and bludgeons, or obstruct the sight of our instruments by holding up trusses of straw, but our surveys were made notwithstanding all impediments, although in some of the worst cases we had to accomplish our purpose at night by the aid of lanthorns; but there were other cases where we received a hearty welcome as the harbingers of future benefits.

These expeditions, at my then age, were most enjoyable, and sometimes not a little exciting; they made one familiar with many charming and remote spots not often visited then by tourists, and brought me into contact with all sorts ind conditions of men, many of whom were noteworthy in many ways.

Then after the surveys were completed one had to attend the Parliamentary Committees, with perhaps Thesiger, the dignified, as counsel for us, and Serjeant Meriweather, the corpulent, against us, and our staff giving evidence—all very instructive and occasionally very amusing. I remember when, on the day of publication of one of the numbers of Pickwick, we were in committee, and the Serjeant was violently opposing us, someone laid before him the illustration of the trial of " Bardell versus Pickwick," with Serjeant Buzfuz addressing the Court. Meriweather, who somewhat resembled the counsel in the picture, looked at it, gave a loud grunt, and went on with his speech.

The drainage of Haarlem Meer was obtained in competition with others, and was carried out in conjunction with Mr. A. Dean, an expert in Cornish mining, the plans being made in our office. The Meer was a large lagoon in Holland, lying between the cities of Amsterdam, Haarlem, and Leyden, in area nearly one hundred square miles, and containing 160 billion gallons of water. This enormous body of water it was proposed to drain by means of three monster steam engines, each of one

thousand horse power, and capable of raising together one hundred and ninety million gallons of water every twenty-four hours. Of course the preliminary works and the construction of the engines occupied some years, so that the pumping did not actually begin until 1848, but the Meer was successfully drained by July 1852, or in the space of about forty months.

Occasionally I assisted in experiments for the galvanization of iron with copper and zinc, with the object of avoiding the use of the costly copper bolts then employed in the construction of wooden ships by the substitution of iron bolts coated with such metals, but the construction of iron vessels rendered the use of copper fastenings unnecessary, and the galvanization of iron is now employed for many other purposes with immense advantage.

We at this time made some experimental trials for the propulsion of vessels by the projection of water at high pressure at the stern, with the view of reducing the wash caused by paddlewheels in narrow channels or in canals, this being before the introduction of the screw, and I am still inclined to believe that such mode of propulsion may be found to possess many advantages.

Amongst other things of interest which came under observation while I was with Mr. Gibbs were his inventions in connection with wood - cutting and inlaying by machinery, which were most ingenious; one of the tools he contrived for forming spirals was said to be the study of the mandibles of the timber - boring marine worm, the Teredo Nevalis.

Of course our office was the resort of inventors of all kinds with all sorts of contrivances, with possibilities of acquiring ** wealth beyond the dreams of avarice "— now a safety lamp, a new paddle-wheel, an improved cab, or a theodolite ; then an artist who would copy you a

Morland or a Hogarth so that you could not detect the copy from the original. But, alas 1 with the majority of such the genius displayed seemed to have been sadly unremunerative.

My professional education, varied as it was (although I was unconscious of it at the time), fitted me admirably for the positions I was subsequently to occupy, for I had often afterwards to rely on my own unaided skill in many things which, had it been obtainable from others, I should gladly have sought; and I have thought myself fortunate, when thrown completely on my own resources, that my education enabled me, when in far remote countries where railways were unknown, to project, trace upon the ground, design the bridges and buildings requisite for a railway, and even, finally, to drive a locomotive (if necessary) over the line when completed.

In Europe there is little need for such versatility, for skill and experience are to be obtained in plenty : judgment in its selection is the principal requisite ; but it becomes a very different matter when one has to instruct inexperience, and resist prejudice where mechanical appliances are unknown, and where novelty is regarded with suspicion.

At Gibbs's my companions were, however, my good friends, and generously gave me every chance of learning as much as I desired. From the two architects in the office one obtained some valuable ideas of design, not only of railway buildings, but in connection with competition designs sent in for the Royal Exchange and St. Giles's Parish Church, Camberwell—which latter proved only inferior to that of Sir Gilbert Scott, a deifeat by no means dishonourable. Another of my old friends at the time, Mr. G. H. Andrews (to whom I shall ever be indebted for my fondness for sketching), became a very distinguished artist, and attended H.R.H. the Prince of Wales on his visit to the United States and Canada.

In the companionship of such as the above, with kindred tastes, we partook of the same amusements, never missing the opening day of the Royal Academy, invariably appearing on the first nights at Macready's Theatre to see " The Tempest," " Coriolanus,'* " Money," " Acis and Galatea," " Richelieu," &c., for some of which the scenes were painted by Clarkson Stanfield, R.A., and where we usually found assembled the celebrities of the times—as Macaulay, Dickens, Thackeray, Carlyle, Lord Lytton, with Charles Kemble and old Liston, the actors of a previous age.

We also had our little sketching-club, to which we contributed an original sketch for criticism, and sometimes I was permitted to enjoy an evening, by the kindness of Mr. Lumley, at Her Majesty's Theatre to hear Grisi, Pusiani, Rubini, and Lablache, or witness ballets in which Taglioni, Cherito, Carlotta Grisi, or Fanny Elseler took part.

On other occasions we attended the Corn Law meetings at Drury Lane to hear the speeches of Bright, Cobden, and others, or went to Peckham to listen to the eloquent sermons of the Rev. Henry Melville, or witnessed a political meeting on Kennington Common (now a park), where I once saw the new police scatter the assemblage by the liberal use of their staves.

Other places of occasional resort were Vauxhall and the Surrey Zoological Gardens; to the latter had been transferred the animals from the old Exeter 'Change in the Strand, which I remember having visited when a boy. These places have all long ceased to exist, are built over, and no trace of them remains, like many other things I have known—as old London Bridge, the old Houses of Parliament, and the old Royal Exchange; but these have been replaced by new and nobler structures, and their disappearance need cause no regret.

In the retrospect of the period of my pupilage—1838-1842—it is remarkable how deficient we then were in such things as, fifty years after, we find indispensable to our comfort and convenience. Then, to reach our places of business we found few conveyances, as cabs or omnibuses, and no railways or tramcars. If we went on a journey out of London we had to travel by stage-coach at ten miles per hour instead of fifty or sixty as now. If we went abroad (as few but the wealthy did) we posted to Dover in our carriage (which we shipped on a tiny steamer to cross the Channel), and posted again over the Continent; while if we had to cross the Atlantic we had to do so in sailing vessels—a voyage perhaps of months, and not of a few days as now. There was no telegraph or electric lights, and not even a lucifer match. Waterproof clothing was unknown, the Penny Post had not been dreamt of, our food was almost exclusively English, and not obtained from the Antipodes; our portraits were cut out of black paper, and not executed instantaneously by the sun. If we required to converse with anyone we had to visit him ; now, however distant he may be, we talk to him through a wire. Gas was hardly known in the suburbs, and the new police had only just displaced the watchmen of Shakespeare's plays. Yet of all the modern marvels we pride ourselves on, how many of them are really new ? Are they not only developments of former notions or contrivances ? Even the popular "bike ** was anticipated by a car on the Croydon line in 1840, contrived by my late lamented friend Sir Charles Gregory, worked by the feet, which was used for inspecting the line. The Electric Telegraph seems to be foreshadowed in a paper (No. 241) by Addison, in 1711, in the Spectator (quoting from a sixteenth-century writer*), describing a magnetic tele-

*Strada.

graph, but mentioning no wires; yet we are beginning to think that even wires are superfluous. We find also in the Harleian MSS. of the British Museum a drawing of a vessel with paddle-wheels, and the Marquis of Worcester, in the seventeenth century, suggested the steam-engine and claimed the invention of a flying-machine. Indeed, the latter eminent personage, with Roger Bacon in the sixteenth century, has been the means of infinite disappointment to modern inventors; and one is reminded of a remark made by a very ingenious man who proposed to us a new form of cab, which we showed him in an old Dutch work on coachbuilding, when he exclaimed, ** Ah! how those Ancients do rob us Moderns ! "

Reflecting upon the marvellous changes that the world has seen in the half-century since my entering the profession of a Civil Engineer, one is at a loss to conceive how we then existed without our present advantages, or what may be in store for us in a like period of the future ; and it is quite possible the enlightenment of to-day may appear as only a gleam of light penetrating the clouds of ignorance which envelop us.

ON RAILWAYS IN FRANCE. 1842—1843.

It would seem to have been my destiny to have been sent to foreign parts, not for my country's good, not perhaps with the view to my own advantage, but, it may be hoped, somewhat for the benefit of those amongst whom I have served ; for I had no sooner arrived at the end of the term of my articles of apprenticeship than I was taken by Mr. Gibbs by a steamer from London to Boulogne, named the City of Edinburgh (Captain Tune),

the same vessel which two years previously had conveyed Louis Napoleon with his Eagle on his ill starred expedition to France, and which led to his six years' imprisonment at Havre, and to his poor old Eagle's confinement at the abattoir, where I used to pay it a visit now and then, as to an historical personage of high lineage.

Being then a good sailor, the voyage delighted me, and on arrival at the quay, the foreign aspect of all around, the martial appearance of the Custom House people, with the ** corps de ballet" fisherwomen gazing on us, and all chattering together, interested me greatly. But what surprised me most was that my school French appeared unintelligible to the natives; but that was a thing soon rectified.

On landing we were evidently regarded with intense suspicion, and it was only after a most rigid investigation we were liberated from the Custom House with our luggage, which was placed on a truck and drawn before us by some of the merry corps de ballet to the Hotel des Bains, then the principal hotel, where we obtained rooms on the first floor in the courtyard, whence we found constant amusement in watching the arrivals and departures of the wealthy and distinguished travellers in their heavily laden carriages, drawn by four big Norman horses with postillions, conveying " mi lord'' and " mi ladi" within, and the maid and courier on the rumble without. The postillions were objects of admiration, as, clad m their glazed hats with cockades, their short jackets braided, their legs encased in enormous jack boots, and their hair tied behind in a sort of queue, the inevitable pipe in their mouths, and armed with their heavy whips, they seemed equal to any emergency; and many were said to perform wonderful journeys, as riding for days at a stretch, even from Marseilles to Boulogne. What became of them ?—ces brave gar9ons.

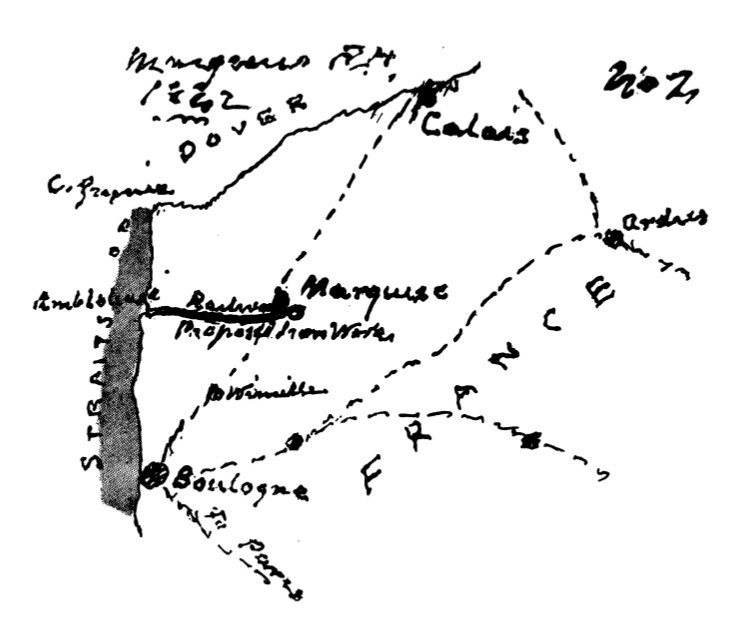

Then France was French; our bedrooms were not too luxurious, the floors were of red tiles innocent of carpet, water was limited in quantity, and soap absent from the washstand—this had to be purchased of the chambermaid, who early each morning appeared at one's bedside with a cup of coffee au laii^ and laid the wood fires which pretended to warm the rooms. Then the neatly attired waiters, and the unaccustomed dishes at the table d'h6te, the novel fashions of attire worn by the guests, all contributed to interest me with the novelties in the town itself— the delightful old walled-in upper town with its shady ramparts and quaint medieval chateau and belfry, the ever changing scenes of the port and harbour—even the fishmarket had its attraction for the lounger, so unlike our repulsive Billingsgate, to say nothing of witnessing the daily departure of the Paris diligences^ those unwieldy combinations of the omnibus, the coach, the postchaise, and the cabriolet, with their biting, kicking, and screaming team of five horses, and its swearing, yelling driver. But we also then could boast of an English four-horse coach on the road to Calais, complete with guard and horn, by which I travelled backwards and forwards to Marquise, where I was engaged in making the surveys of a large ironworks, and of a proposed line of railway thence to the port of Ambleteuse.

The road to Calais had its interest, although the country is not attractive, for one passes by the place where Napoleon collected his huge army for the threatened invasion of England ; we go through then the little hamlet of Wincile, with its humble church and graveyard, where lie the aeronauts Rosier and St. Roman, who lost their lives here in 1785 in an attempt to cross the Straits of Dover by balloon, and at about halfway to Calais we reached the small town of Marquise, known for its marble and large iron-smelting works, at that time idle.

Here I was engaged for some time, occupying quarters, primitive enough, in the humble auberge of the place, ivhere I was kindly entertained, and fed sumptuously on wild ducks and fieldfares, which abounded in the vicinity, •especially along the course of the railway I was sent to survey, beside the little river Slack, which, traversing some broad marshy lands, flows into the sand-choked harbour of Ambleteuse, historically interesting as the landing-place in 1688 of the unhappy king of England, James II., on his flight after dethronement, and as also one of the places used in the preparation of the flotilla for invading England in 1803, abandoned wisely; but the place when I was there presented the most forlorn and melancholy aspect, containing only a rotting mildewed fort or blockhouse, some skeletons of timber moles, but nothing living to be seen except scores of wild rabbits.

Boulogne, where I remained for two or three months, was a very quiet place in the winter of 1842, but by no means dull. As yet the railway from London to Dover was unfinished, and that from Boulogne to Paris was not commenced; tourists were few, and travelling carriages seldom seen, but we had a theatre, the caf6s and their billiard tables, and, above all, the residents to study and amuse us; for they were of an infinite variety, and almost all of fairly good appearance, but practising a rigid economy; a number bore a rather horsey look, most of them were rather fortunate at games of skill, and I think they all appeared to have enjoyed the intimacy when in JEngland with members of the aristocracy.

For a while at Boulogne I resided with the editor of the newspaper, who was married to an excellent lady, who, like most of her countrywomen, was an admirable housekeeper; with them I lived thoroughly d la Francaise^ and on one occasion, specially for my benefit, a dish of fricasseed frogs was provided, but failed to meet with my

approval. While with them I made a trip to London by way of Dover, thence by mail coach to Headcorn, and on to the Metropolis by the South-Eastern Railway, thus far opened for traffic. On my departing on this occasion I was commissioned by the editor to apply to Rowlands for payment of arrears for advertisements of the Macassar oil, and by Madame to procure for her needles and cotton stockings, all of which I duly complied with—I hope successfully. During my stay at Boulogne I was visited by a party of my engineering friends who had come from London to witness the destruction of the Round Down Cliffs at Dover; among them was the late Sir Charles Gregory.

This, the first of my unassisted engineering experiences, was invaluable to me, besides leaving behind it many pleasing reminiscences, with an affectionate regard for a people I have found act kindly to me, who possess transcendent abilities in literature, science, and art, and who have numerous inestimable qualities besides to recommend them.

To Paris, upon the Construction of the Great Northern of France Railway.

Having completed my work at Marquise, instructions came for me to proceed to Paris; therefore, early in 1843,1 secured a seat in the coupe of the Paris diligence leaving Boulogne at five in the afternoon for the capital. It was a journey I had long desired to make, for should I not pass near the glorious battlefields of Crecy and Agincourt? and travel over the ground of Sterne's " Sentimental Journey," by Montreiel, Nampont, and Abbeville ? But I was alone in my coupe, and the uneven road rendered sleep impossible when in motion, and when we stopped to change horses the screams and shrieks of the great

Norman cattle, with the yells and cries of the ostlers in attendance, effectually put an end to slumber.

However, the following morning we lumbered into the city of Beauvais, where we had breakfast, and had afterwards time for a hurried visit to the noble cathedral of the thirteenth century, the choir of which is said in height to exceed considerably that of Westminster Abbey.

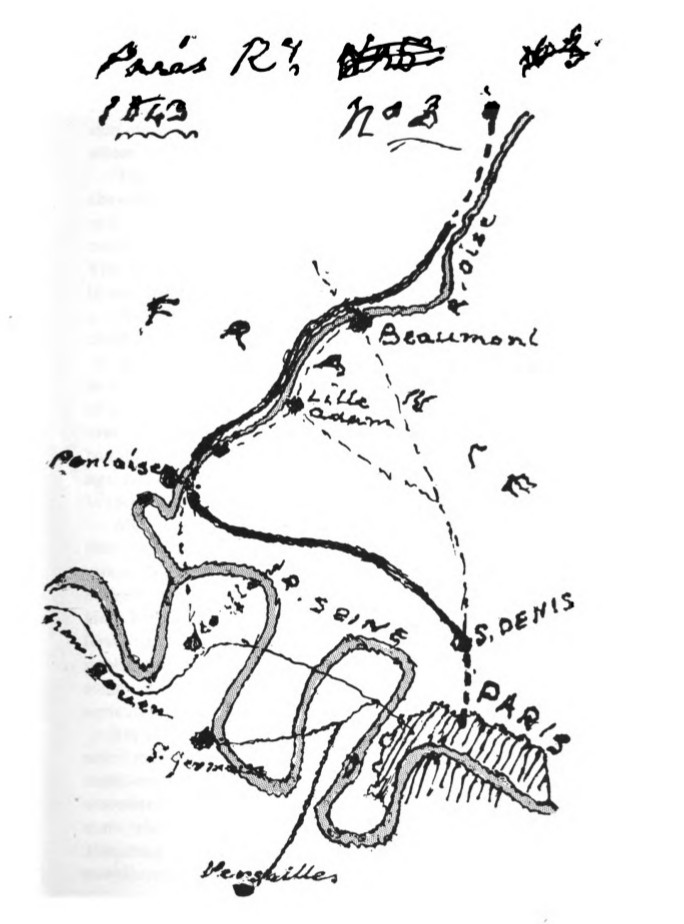

With a great cracking of whips and a torrent of choice expletives by the driver, we proceeded on our way—after leaving one of the few cities in this part of France besieged but ttot taken by the English—over paved roads and along endless avenues of poplars until we came to the Oise River, which we crossed by a good bridge, under which great barges with huge rudders were on their way from Paris into Belgium, the proposed railway from Paris to the North crossing the high road close by the bridge; and it was here I subsequently began my section of the line.

The town of Beaumont stands pleasantly upon rising ground at the end of the bridge, overlooking the river, and in this clean and salubrious spot I afterwards resided for some time agreeably enough. The road after leaving Beaumont offered little that was attractive beyond the increasing wayfarers with their blouses and sabots, for we soon approached the city of St. Denis, with its ancient church—the desecrated sepulchre of kings—and thence the signs of our nearing a great city became conspicuous enough, and at length, at about 6 p.m., after twenty-five hours of sleepless torture, our " bone-setting " journey came safely to an end, and I sought refuge in the Hotel de Lille et d'Albion, which then stood on the site of the Louvre, and, I believe, almost facing the royal mews of the then king, Louis Philippe, afterwards dethroned in a revolution, which in Paris are almost as frequent and infinitely more sanguinary than in a South American Republic.

I was unable then to see much of the city or its curiosities as subsequently, for I was almost immediately appointed to assist in the proposed railway from St. Denis to Pontoise and Creil. There then existed one short line out of Paris—that to Versailles, with branch to St. Germain—and the line to Rouen was in course of construction by the eminent English contractor, Thomas Brassey, under the direction of Joseph Lock, C.E. The line to which I was attached was the first main line undertaken by the Government out of Paris, was under the superintendence of the Engineers of the Ponts et Chauss6es, and the works were let to English contractors, with certain limitations as to number of foreign labourers; so that, at under twenty-one years of age, I shared in carrying out the third railway opened out of London, and the third also out of Paris, and I feel some pride in having been one of the early pioneers of a system of communication from which has been derived such incalculable benefits to the entire globe.

We therefore, with only a brief delay, set out from Paris for Pontoise, where we found excellent accommodation at the Hotel du Grand Cerf, by the bridge over the Oise River, where we remained until we secured more commodious quarters at a neighbouring chateau close by the works.

The hotel was a good example of a French provincial hotel. It was managed by a cheerful, bustling woman ; there was no male, as far as we saw, in authority. The chief entrance was into a spacious kitchen, where the chef displayed great dignity in front of his fire. In the centre of the room, which was scrupulously clean, was a huge table, on which was displayed attractive!}' and ready for immediate use the viands for the day, thus offered for inspection and selection by the customers—fresh fish, cutlets, breaded and larded veal, poultry, fillets of beef,

&c., interspersed with fruit and vegetables, all skilfully arranged and appetizing in appearance, so that the guest obtained an assurance not only, of the soundness but the genuineness of what he partook of, which printed menus sometimes fail to do. Thus our repasts seemed perfect, especially as the waitress, Lisette, with her bright and merry looks, would have dissipated the gloom even of a City chop-house during a November fog.

Our rooms looked out on the pleasant river, on the further side of which stood a fine old chateau, but which had been converted into a Hour mill; and behind this, upon the hillside, rose the city of Pontoise, culminating in a mound where once stood a castle-keep, besieged and taken by our countrymen in 1491, the site of which had been converted into a charming garden, while the mound of the keep, affording a most extensive view, was made use of for practising on the cor de chasse (French horn), where quite a number were to be heard in full blast.

From the hotel, after a while, we removed about a mile away to the Chateau d'Epluche, which stood on high ground overlooking the valley of the Oise. It was approached by an arched gateway, having wings on either side containing stabling, granaries, &c. Within was a large courtyard, at the end of which stood the chateau, and on one side was a large shrubbery (or so-called English garden) which was a favourite resort of nightingales and huge snails, which were considered by epicures especially suitable for making potage d'escargot (snail soup), and they were collected by the porter and dispatched to Paris, adding to the revenue of the chateau in addition to supplying the larder of the owner, who was said to be a banker of St. Denis, and who lived here en garcon, having, in accepting us as tenants, reserved two rooms for his own use, passing the whole of his time (his wife managing the bank) in shooting the nightingales, I fear, capturing

t*^nl»'\.

^

snails, and in smoking a very black pipe, and, I fancy, living en pension with the porter, for we had entire posses-^ sion of the kitchen, where Lisette from the hotel presided whom we had engaged as housekeeper and cook.

The chateau itself was a long building of one story^ above the basement, and some attics in the high mansard roof. The principal rooms were lofty and spacious, but comfortless; the rest were very inferior in every way. The house was convenient to the heaviest wolrk we had to execute, which consisted of deep rock excavations and a large bridge crossing the river Oise, which was to be chiefly of stone, of which an abundance was obtainable on the opposite side of the river from a quarry belonging-to an old General, with whom I had often to treat for it of a morning, whilst he, scarcely dressed, was sitting^ over his fire in very humble quarters, preparing his bouillon, or soup, for the day. He was over 60 years of age, looked a thorough veteran, and might have been at Waterloo with Napoleon.

After residing for some time at the chateau, we received orders to commence work at Beaumont, and I was sent there in charge. On my arrival I found myself entirely unprovided with men, tools, or materials of any kind, but with peremptory orders to employ 300 workmen forthwith. I was at a loss, but it occurred to me that a public notice, if posted up in the town, might induce some of the peasants around to assist with their agricultural implements.

Such a notice was made public forthwith, and the next morning, agreeably to my surprise, when we made an appearance at the spot indicated, there was assembled a motley crowd of volunteer navvies, numbering more than a hundred, with every species of earth-disturbing implement, and with a perfect collection of wheelbarrows, many of remote antiquity.

With this force we began our task, and soon our numbers increased, and the work went on briskly enough ; but as there was no communication with our headquarters at Pontoise, I purchased at a farm, near by, a pony, which I took away amid the lamentations of the entire family, who clung round its neck with sobs and tears, and implored me to be kind to their pet, and bring him often to see them.

Thus I was enabled weekly to reach the chateau for the means to pay the workpeople. It was a ride of about twenty miles there and back, partly through forest, where the charcoal-burners bore an indifferent reputation ; then through the village of Lille Adam, a charming spot on the Oise ; and after over open country to my destination. Before returning I had to pay a visit to the bank ai Pontoise, to obtain a sackful of five-franc pieces, which I slung across the saddle, and, having paid my respects to our amiable banker, who was, as usual, a lady, I returned to Beaumont, too late sometimes to be pleasant or very safe with the burden I conveyed.

With the workmen in general I got on pretty well, but of course they were altogether inexperienced, and I was only allowed six Englishmen on my portion of the work, so that having an offer of a party of Belgians who had seen similar work executed, I readily engaged them, and thus planted the seeds of rebellion: for while at breakfast the following morning one of the Government inspectors rushed in exclaiming that murder was being committed amongst my men, and that I must proceed at once to quell the disturbance.

Somewhat startled by such alarming intelligence, I hurriedly finished my meal, and went to obtain assistance at the gendarmarie; but none was to be had, for the whole force had gone to Paris with prisoners, availing themselves of the occasion, it being the King's Birthday F4te :

therefore one had to make the best of it and personally try what I could do. On passing over the bridge to reach the work, I encountered the whole of the men—about 300 French and Belgians—on their way to interview me, all in the greatest excitement, and making a fearful demonstration of their discontent with every thing and person not French. I at once addressed the Belgians, demanding why they were not working. They declared the French threatened them with death if they did, so I ordered them all to return with me so that I might ascertain who would attempt to interfere. So they all followed to the spot where the riot had broken out, which was found deserted by all but my gang of six English navvies. On our arrival, in my best French I endeavoured to pacify them, but seemed only to inflame their passions, for from violent abuse they proceeded to brandish their spades and pickaxes in a most energetic manner, while some ventured to suggest violent measures. Then to my side came my chief English navvy (a splendid specimen, named Tom Breakwater, from having come into the world on the Plymouth Breakwater), who had observed their threatening gestures, and asked me what they were saying, and, when I told him they proposed throwing me into the river, coolly remarked, " Never mind, master, rU pull you out."

Seeing, however, that the men were deaf to reason, I decided to suspend work altogether for the time, and I made it known that as it was the King's f^te-day we would all take a holiday, a proposal which met with unanimous approval, and we all went into Beaumont, where we proceeded to a timber merchant's to purchase some materials, and, having done so, were invited by the owner to take a glass of wine, and, accepting his hospitality, entered his house, which proved to be a wineshop, wherein was assembled the ringleaders of our

mutiny, but who now, instead of desiring to plunge me into the river, wanted to drown me in the bowl; so I drank with them, proposed the health of the King, and wished them and France all prosperity.

The next day the Government engineer returned, and several of the men were arrested, but at my intercession they were soon liberated, and tranquillity was assured.

At the works of the Oise Bridge we had a much more serious affrav between the French and Belgians, which resulted in the loss of several lives, after which we had piquets of cavalry posted along the line to maintain order.

During this stay in France I enjoyed many visits to the capital—now half a century ago, before it was annexed by Americans and Cook's tourists, and before it had been restored by Baron Hausseman; its picturesque features, so quaint and antique, destroyed; its historical monuments, in many cases, razed to the ground ; and so much of its romantic interest dispelled by the ravages of the improver, and the destructive insanity of Communists. It now may be a handsomer and perhaps a wholesomer city, but one regrets the loss of things and objects intimately associated with the history of a country and people so interesting.

Riding from the chateau to the station of Confleurs on the newly opened Paris to Rouen Railway in the forest of St. Germain, I was enabled to dispose of my spare time in making acquaintance with even the most obscure and retired places in and around the ** Ville Lumiere," which yielded me much satisfaction and instruction ; and on the completion of my section of the work, at the close of 1843, I returned to England by way of Rouen and Dieppe, and thence by steamer to Shoreham, the then port of the Brij^hton Railway, the easiest way then home, and still, one believes, the most agreeable and attractive if not the most expeditious.

PRACTICE IN ENGLAND. 1843 to 1848.

The period of my return to England from France was one of great activity in the railway world, so that one soon found an engagement in surveying some of the then projected lines. That proposed from Salisbury through Shaftesbury, Sherborne, to Yeovil (now forming part of the South Western to the S.W. of England) was the first —thus I became intimate with these towns, and with many of the objects of interest in their vicinity, such as Old Sarum and Stonehenge, of which an American, when asked what he thought of it, declared, ** Wal, its very rustic! " The ruined Fonthill Abbey—the sad relics of ambitious folly of the author of " Vathec *'—with its weed-covered lawn and neglected plantations; the fine old Minster of Sherborne and its ruined Castle, once the dwelling of murdered Sir Walter Raleigh; terminating this excursion at Yeovil, where I first went after the foxhounds on a hack hired at the inn, and fell in leaping into a newly gravelled lane, and had to return to town across Salisbury Plain on a bitter night late in November with an injured knee.

A similar engagement took me over the country between Bath, Wells, and Glastonbury, than which three places, so near to one another, there can be no greater contrast; in the modern fashionable aspect of the first, the mediaeval appearance of the second, and the moss-grown crumbling ruins of the last. At another time Dorchester, with its Roman remains, with Weymouth and the Isle of Portland, demanded my attention.

Early in 1844 I joined the staff of Frank Giles, C.E., whose chambers were next door to the College of Surgeons, Lincoln's Inn Fields, and whose practice was

mainly connected with Mr. Robert Stephenson, C.E., M.P.; and this engagement, ultimately, to my great delight, procured me the honour of becoming associated with that distinguished engineer.

As Giles's we worked from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. without interval for luncheon, and the scarcity of transport from my residence at Vauxhall obliged me to walk five miles to and fro daily. No Saturday half-holidays were then thought requisite, but we seemed none the worse for their absence, but we always were rejoiced to obtain occasional duty in the field, especially as then our pay was doubled.

Mr. Giles was one of the first, as far as I am aware, ^o originate the idea of underground railways, for in 1845 I made for him the plans and sections of a proposed line from the North Western Railway at Mornington Crescent, Hampstead Road, moving south behind the Tottenham Court Road to the then Brengerford Market, now the Charing Cross Station. These investigations had to be made soon after daylight, before the traffic began, but when the latest night-birds had yet unsought their roosting places.

This project was, I think, then considered premature, but would now have been most advantageous and beneficial, for Charing Cross would have been the central station for London from the north and south, would have provided a direct communication through the Metropolis, and saved millions annually in the transportation of passengers and goods.

Its execution ^yould have presented no difficulty of a serious nature, for it only interfered with one sewer, that under the Strand, and the properties affected by it were mostly of no great importance at the time.

The year 1845 was that of the " Railway Mania,'* and of exceptional activity in all departments of such enterprises. Every engineer of ability, with many of no

>

29

PRACTICE IN ENGLAND.

ability whatever, were engaged on all sides; and we were hurried from place to place with scarcely time to take a meal or seek a couch. Travelling by night, and plodding over the country all day, so that, in consequence of such feverish haste and the employment of unskilled persons, the result was inevitably the rejection of many such schemes through inaccuracies in the plans or failure in their preparation in time.

Our lives at such times were one perpetual trespass; no property, however sacred or private, of noble or peasant, was regarded by us as such. We penetrated into the most exclusive pleasure grounds, perforated garden walls and fences, roused the game in strictly preserved plantations, no doubt doing some damage and rousing some bitterness of feeling, which I trust has been amply compensated for by the benefits since derived.

I fear we were not generally popular, for many opposed us with active resistance or violent threats, so that we sometimes, to thwart our opponents, were obliged to resort to stratagem, working by lamplight when our adversaries were slumbering, and even on Sundays when they were better engaged, for some of our most energetic objectors were of the Church, but who in vain resisted the great social revolution, which has done more for brotherly love and international harmony than all the lectures ever delivered.

At one time during this period I was on the Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway, when I became acquainted with Sheffield the grimy, Worksop, the neighbourhood of the Dukeries, Retford, and the grand old cathedral city of Lincoln; at another time I found myself among the burning cinder heaps, between Birmingham and Dudley, and through the country of Coalbrookdale, by Buildwas Abbey, past the Wrekin to Shrewsbury. Another time to regal Winchester, to partition the water of the River

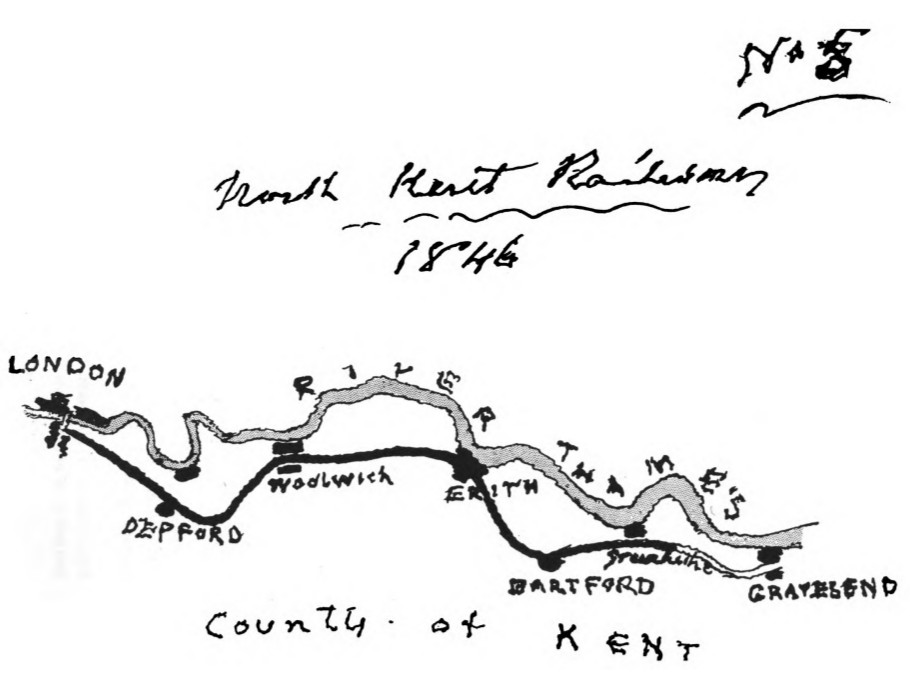

Itchen between rival millers, and in similar excursions, with intervals of office work in designing bridges, &c., for railways then in construction. My time passed away until the early part of 1846, when my opportunity came, and I became connected with the most eminent member of my profession, Robert Stephenson, M.P., by whom I was favoured with instructions to set out upon the ground the North Kent Railway, then about to be commenced from London to Gravesend, through Deptford, Woolwich, Dartford, and Greenhithe, and this, in conjunction with my friend the late Frederick Turner, C.E. (afterwards the engineer of the London, Chatham, and Dover line), we duly accomplished.

Kent was always a favourite country of mine, thus to help to execute works of utility amid its pleasant and varied spots of rural beauty and historic interest was a pleasure; therefore, with much gratification, I received the offer of the appointment of resident engineer when the works of the railway were commenced by the contractors, of whom there were two, Mr. John Treadwell and Mr. John Brogden, both gentlemen of well-known ability.

AS RESIDENT ENGINEER ON THE NORTH KENT RAILWAY.

1846.

On this line the works were of an interesting character. My section commenced at London Bridge, and consisted of a further widening of my old acquaintance, the Croydon Railway, from which it diverged across extensive market gardens to Deptford, where massive retaining walls were required; it then passed under Blackheath by

\

a long tunnel in clay, a work which was rendered necessary by the astronomical authorities of the Observatory, who opposed us passing then under Greenwich Park, as the line now does, from fear of disturbance of their instruments, a fear which has proved groundless. Beyond this tunnel the line ran below Charlton and through Woolwich (where again heavy retaining walls became necessary), until the Arsenal gates were reached, when it entered the Plumstead marshes and ran on to Erith Old Church, and thence through the town and on to Dartford; on approaching which place we discovered in a cutting through alluvial soil, the fossilized remains of a number of antediluvian animals, such as elaphas insignis, rhinoceros, deer, &c., which were submitted for inspection by Mr. Stephenson to Dean Buckland at the time. Kent was prolific of treasures of the remote past, for such were often met with; quite extensive discoveries of funereal Roman urns were unearthed beyond Gravesend and also near Richborough.

At Dartford the work was of importance, consisting of bridges, retaining walls, and a deep excavation in chalk, therefore I made the town my headquarters, and stayed for some months at the old Dover posting house, " The Bull," which was one of those ancient hostelries where the bedrooms were reached from galleries, as in Shakespeare's time, and might have sheltered him, if not the Canterbury Pilgrims. It was entered beneath an arched gateway, under which hung invitingly large joints of meat, poultry, and game. There was an old-world look about the place and of cheery welcome, even its one-eyed boots, who we believed was its last surviving post-boy, was in keeping with the house, in which many pleasant hours were spent by us.

Beyond Dartford the line reached Greenhithe, and there we had a second tunnel through chalk, at the end

of which my section of the works terminated near Gravesend. They were enjoyable days passed on the North Kent. I had a good horse, on which I made now and then a visit to my home in town, or made trips to Gravesend, whence we took sailing excursions to the Nore and back, returning late to Dartford, our way cheered by the songs of nightingales ; and one day, seeing a crowd in the marshes by the Thames, went to view a prize fight between two celebrated pugilists, for which we paid for front places, viz., a handful of straw, from which, as the fight was coming to an end, we were dislodged by the unruly and most disreputable mob assembled around us.

Unfortunately, before the completion of the works, Mr. Stephenson resigned the position of chief engineer, and was succeeded by Mr. Peter Barlow, who afterwards designed and constructed the Lambeth Suspension Biidge, probably the ugliest structure of its kind existing. I was offered the privilege of remaining in my post, but I naturally preferred to follow my great and venerated chief, a decision never regretted by me afterwards.

I parted from my able, hearty, and industrious associates of the works with great regret; but before my departure the principal workmen insisted on inviting me to a supper, at which they presented me with a handsome silver tankard, as they said for me " to drink my beer out of," on which their names were duly engraved. Amongst them several afterwards acquired considerable distinction, and secured handsome fortunes, to which they were well entitled.

This supper was, I am disposed to think, rather a noisy one, but did not pass the bounds of propriety, though the songs were stentorian and the horseplay somewhat rough. I call to mind the chorus of one of the songs of a Dover boatman, which was done full justice to it may be believed.

It ran thus :—

No 1 deuce a bit, said Jolly Jack of Dover,

No more of those infernal French will ever I bring over.

And I remember that veritable Samson amongst them, who the whole party failed in an endeavour to put in the chair, so that they might carry him round the room.

Railway contractors of those days in many instances were uneducated men, but I have ever found them warmhearted and trustworthy. Many stories are related of them when they became wealthy, as evidence of their inexperience. One I knew, an excellent fellow, having bought a noble mansion with extensive grounds, desired to adorn the place with some what he called " Stattys,'* and sent an agent for the catalogue of a sale, about to take place on the Marylebone Road. He duly complied, and they both examined it together, but it was unintelligible to both. Lemprierewas to them a sealed book, Ganymede and the Graces, Psyche and Pan, Juno and Jason were all equally unknown, and the worthy contractor, unwilling to confess ignorance to his subordinate, settled the matter thus: ** Well Dick,you'd better go and buy the whole lot,'* which accordingly was done.

Another well-known example of industry and affluence found himself at a palatial railway hotel at midday, and demanded a plate of soup. ** Soup sir, yes sir," said the waiter, **What soup would you like, sir?" "Which is the best soup ? " asked the guest. " Well, sir," answered the other, " turtle soup is the best, sir." " Then bring me some," ordered the visitor, not having heard of such soup in his life before. The soup was served, and was so much approved of, our maker of railways ordered a second and even a third plate, after which he asked for the bill, which he found amounted to fifteen shillings. " What's this," he inquired of the waiter, ** Is this soup five shillings a plate ?'" " Yes, sir," answered the waiter with

3

2L chuckle, " turtle soup is five shillings a plate, sir," and no doubt thinking the guest would feel somewhat amazed; but the guest astonished him instead by pulling out a well-filled purse, and saying, " Well, bring another plate to make up the pound."

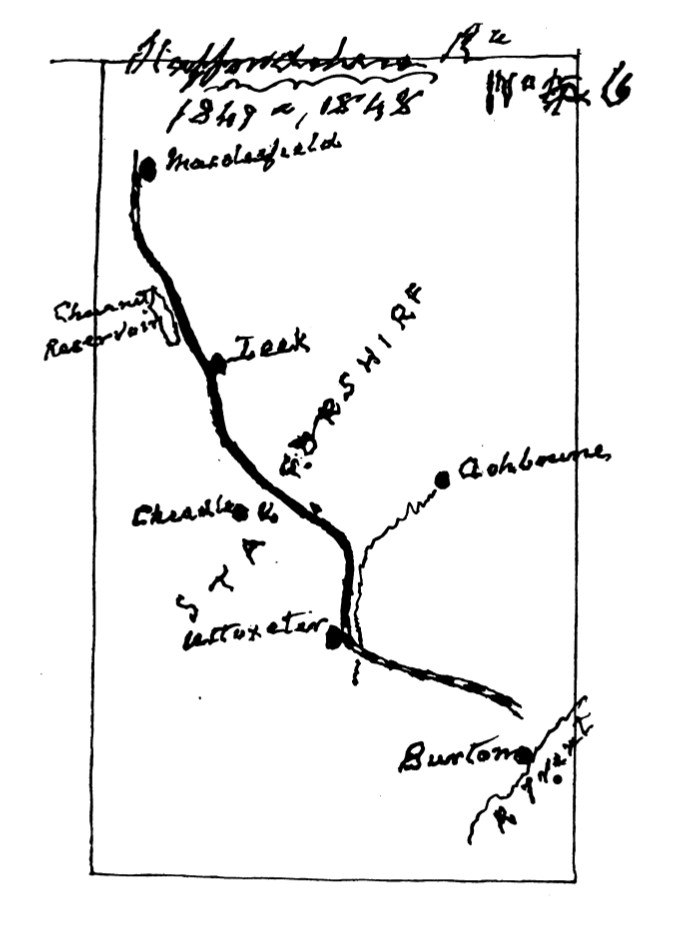

AS RESIDENT ENGINEER ON THE CHURNET VALLEY RAILWAY, STAFFORDSHIRE.

1847.

In the Autumn of 1847, having been appointed to •superintend the works of the above Railway, I proceeded to Leek to take charge of the line for Mr. Stephenson in the vicinity of that place, and proceeded to that pleasant Midland town to make arrangements for the reception of my family, soon after to join me from London. Leek then was rather a retired spot; its nearest station was Whitmore, on the North-Western Railway, fourteen miles distant, whence we had to post through the Potteries to reach our destination, where we arrived half-frozen, to find the quaint old house I had secured the picture of comfort, with blazing fires in every room, and a plentiful repast provided by my valued friend and assistant, Harold, who some years after fell a prey to the climate on the Indian Peninsular Railway, where he was one of the engineers.

My sojourn at Leek extended over two years—very agreeable ones—in a clean, healthy town standing in an •elevated position on the old red sandstone formation, and where we soon met with pleasant friends. The works under my charge were interesting, and the surrounding ■country was picturesque and most attractive, offering ample scope for the pencil.

We had within our reach some of the most beautiful scenery of Derbyshire at Buxton, Matlock, Dove Dale, &c. ; the noble demesnes of Alton Towers, Trentham, and Chatsworth, with the porcelain wonders of the Potteries, or the silk manufactories of Macclesfield ; and were not too distant from Manchester so as not to be able to attend an Oratorio with Jenny Lind, or join a Meet with Meynal Ingram's foxhounds at Uttoxeter. But our work was never neglected, but proceeded with all possible energy by our worthy contractor, a brother of John Tread well of the North Kent Line, and a gentleman of great practical ability, who afterwards undertook the execution of the works of the ascent of the Bolne Ghauts of the Indian Peninsular Railway, and succumbed to the climate during their execution, when his young and clever wife, the daughter of another contractor, bravely undertook to complete her husband's contract, and accomplished it, acquiring fortunes for her children.

During our stay at Leek I had opportunities of visiting Chester, Bolton Abbey, Worcester, Ashby de la Zouch, with other places, and during the time made acquaintance with the Colossus of Railway Contractors, the late respected Thomas Brassey, who was a man of the kindest and most amiable disposition, of immense tact and ability, and who well deserved his success.

It is related of him that when Sir Samuel Peto failed he offered him his assistance with £"300,000, which Sir Samuel gratefully declined, saying " It would only be a drop in the ocean." Such an offer from a friend is unusual, but perhaps more rare to be declined. Sir S. Peto's failure was due to his departure from the legitimate business of contractor, and becoming financier also, which, I thmk, Mr. Brassey never did.

I went once with Mr. Brassey to visit the wreck of a

N

36 A RAILWAY PIONEER.

viaduct, over 100 feet in height, which he had built, and which had in great part fallen when just completed, and which presented an awful scene of loss to him as con-^ tractor, but he never uttered a word of complaint or annoyance, and when our inspection was finished I expressed my sympathy with him on the disaster. I ventured to offer my opinion that I thought no fault was apparent with either the workmanship or materials, and asked him " What he proposed to do ? " " Why! set ta work and build it up again," he replied calmly, and gave orders accordingly, and I am glad to say that the collapse of the work was subsequently proved to have been caused by circumstances for which he was in no way accountable.

Among the works under my charge was a tunnel through the sandstone, which had two shafts worked by one steam engine between them, so as to lift the skips or buckets from both, the descending skips being lowered by brakes. I had just gone down one of these shafts, and was standing below, when the next skip containing several miners came down with fearful velocity, and the poor fellows were dashed dying and dead at my feet, the brakes above having failed to act through negligence of the attendant.

At another time, when on a locomotive passing over an unfinished bridge, the engine left the rails, and we most narrowly escaped being precipitated into the River Chumet beneath us; and again, whilst examining a slip, over another tunnel on this line, the rocks and earth began to shower down upon us, and we escaped death only by a miracle, as the slip soon extended up to the surface of the ground 150 feet above the railway. This, slip was, however, instructive to me afterwards in South America. Such as are employed on great public works. must necessarily incur risks, but perhaps not greater thaa

'encountered by the wayfarer in a crowded street of the Metropolis.

An interesting feature on the line was the Rudyard Reservoir, a veritable and beautiful lake, along the side cf which it ran for about two miles under steep larch-covered hills, an attractive feature on this work—but not by any means the only one, for many positions were extremely beautiful, particularly around Alton (with its great monastery, built by Pugin for the Eairl of Shrewsbury), Tutbury Castle, &c., while numerous things of antiquarian interest in the vicinity gave ample means of amusement and intellectual study.

Altogether our experiences of Staffordshire were pleasing in every way, and upon leaving it, on the completion of the work, we experienced sincere regret, and the reminiscences of our sojourn will ever remain green in our memories.

On returning to London I resumed my position in Mr. Stephenson's office, which then occupied the position in Great George Street, Westminster, where now stands tfie new and handsome Institution of Civil Engineers.

IN THE OFFICE of MR. ROBERT STEPHENSON.

1848 TO 1853.

During five years I remained constantly in this office, whence issued the designs for some of the greatest, as well as of the most original, of the engineering works of the age, or with matters connei:ted with the numerous railways then in progress under his able management. We occupied three floors of the house, the ground floor being that occupied by Mr. George Parker Bidder, C.E., who had begun life as the celebrated calculating boy.

of whose wonderful powers of mental calculation I had many proofs. He was associated with Mr. Stephenson in many things, and was invaluable in conducting Bills before Parliament, and, if somewhat rough in manner and address, showed me much kindness, when I least expected it. He seemed only to have an engineering secretary^ and was always reading the Times and smoking a good cigar, when cigars were less found in offices than now. Mr. Bidder could mentally extract the square and cube roots, and once multiplied 12 figures by 12 figures, which he said was " hard work."

The first floor of the house of three rooms were Mr. Stephenson's, one his secretary's, next the chiefs private room, with consulting room adjoining; and on the second floor the nephew of Mr. Stephenson, George Robert,, presided over myself and one or two others. This completed the stafi", and I have often wondered at the work accomplished by so few of us. For at this time the designs were in hand for the Great Victoria Bridge at Montreal, the Benha Bridge of the Nile, with numerous others of less importance.

Then there were duties occasionally elsewhere, such as a visit to Belgium, where we were entertained by the Minister of Public Works to an elaborate banquet, and when, having gone to Wavre, we made a pilgrimage to Waterloo ; or being at another time despatched to make a survey of part of the Wash, Lincolnshire, in connection with the outfall of the Nen River and the Bedford Level Drainage, I stayed at Sutton Bridge and Wisbeach, and cruised about in a fishing smack hired for the purpose, which enabled us when at leisure to dredge for the strange and often repulsive creatures of the deep; and when exploring the drains, investigating the aquatic vegetation which flourished in the placid waters of the dykes of these otherwise unattractive Fens.

At one time I was entrusted to report on a system of drainage for the rapidly expanding town of Middles-borough, in Yorkshire, for the distinguished Quaker^ Mr. Joseph Pease, M.P., who showed me great kindness while thus engaged. 1 found him a man of high worth and intelligence, and well worthy of the position he held of the founder of a thriving city. This investigation interested me profoundly, for it made me acquainted with the parent passenger railway, that on which George Stephenson, the father of my Chief, gained his first triumphs, and inaugurated the system which has done so much for the happiness and welfare of the whole universe.

At another time I was engaged for some weeks in computing the amount of work executed on the Chester and Holyhead Railway at Bangor, and thus had an opportunity of examining the two colossal Bridges of Telford and my Chief, Robert Stephenson, over the Menai Straits, with that by the latter beside the old castle at Conway ; our Sundays being spent in exploring Snowdon, or in visiting Carnarvon, Beaumaris, Harlech, and other of the many objects of note in the vicinity.

We had quarters at the George Hotel, where we had a sitting-room appropriated to the engineers of the line, and it was, I believe, the only apartment in which Miss Roberts, the admirable hostess, permitted smoking; and here on one occasion Thomas, the Sculptor, and John Leech, the Punch Artist, were together, the former reclining on a couch enjoying his pipe, while Leech sat at the table looking over the Visitors' Book, and while doing so he amused himself by making one of his inimitable sketches of "A British Lion enjoying of Himself." It represented a lion, such as Leech only could pourtray, lying on a couch, with an expression of intense enjoyment, smoking a long clay pipe, his legs crossed, and his tail thrown

gracefully over his loins. Thomas was the sculptor of the lions of the Britannia Bridge, and also of the Houses of Parliament.

During 1851, while surveying a line of rail from Boston by Sleaford to Grantham, I listened to the bells of the churches tolling for the funeral of the Duke of Wellington, whose lying-in-state I had seen before leaving town ; and in the following year I was engaged on the East Anglian Railway, and gave evidence before the Parliamentary Committee of the House of Commons on the Bill.

In 1852 I undertook the drainage of Watford, which was duly executed, and also reported on that of Banbury, which, however, was hardly ripe for execution, when other business of greater importance absorbed my attention, for early in 1853 a powerful combination of capitalists appointed Messrs. R. Stephenson and Bidder to prepare a project for supplying Sweden with railways, and 1 was summoned by Mr. Bidder to undertake the task of preparing the plans of seven hundred miles of railways for submission to the Diet of that Kingdom.

I was informed of my appointment to this business early one day, with the intimation that the steamer would leave Hull for Gothenburg the next morning, and that I had better prepare at once for departure. So, having done so, I returned for final instructions, which I obtained from Mr. Bidder in his most characteristic manner.

Said 1, " I am quite ready to start." " Well," was the reply, " Don't go and make a fool of yourself"; and on my indignantly demanding to know if " I had been in the habit of doing so in my work," he rejoined—" No I or you would not have had this appointment"; and he then explained that Robert (Mr. Stephenson) and he had recently recommended someone to a post in Egypt, where

their nominee had immediately started a four-in-hand, and displayed total want of common sense, and causing those who recommended him much annoyance.

SURVEYING IN SWEDEN.

1853.

Having received these specific instructions, with a map of Sweden, I left London by Mail train the same evening for Hull, where the next morning, before daylight, I went on board the steamer Scandinavian forthwith to sleep. We soon made way out of the Humber, and, after experiencing the playfulness of the North Sea for a couple of days or so, eventually sighted the north coast of Denmark, where lay a recent wreck; we crossed the Cattegat and entered the port of Gothenburg.

Of course, I was utterly ignorant of the Swedish language, therefore an interpreter was requisite, and I found one in a young English gentleman, the son of a merchant of the city, a Mr. Seaton, who I engaged, and who afterwards became an able engineer. With him I explored the city and neighbourhood, which repaid us well for the trouble. It was odd to find oneself reading the paper at almost midnight. It was strange to find the floor of our room at the hotel strewed with green pine tops instead of carpets, and it amazed us to discover that lobsters and strawberries could be had for almost nothing.

At that time a short piece of railway had been begun by Count Rosen (an Admiral in the Swedish Navy) from Orebro towards Westeras, and this it was intended to extend to Gothenburg on one side, and to Stockholm on the other, so as to form a communication across the country by way of Falkoping.

A second line was to be surveyed from the latter city southwards, by Jonkoping to Lund and Malmo, opposite to Copenhagen, with a branch to Christianstad; and in addition to these lines from Stockholm was another proposed line, by Upsala to Gefle, on the gulf of Bothnia, and to Fahlun, the mining district of the north, a total of about 700 miles of survey, which had to be made before winter set in, as then operations would be impossible. Therefore, as winter might be expected early in December, the surveys had to be completed in five months, so that no time could be wasted, and, consequently, we had to take the first available means of reaching Orebro by the canal and lake steamer.

This part of the journey was very enjoyable; the steamer, commanded by a Naval officer, was a comfortable one, and the river scenery was very attractive as we ascended to the foot of the Falls of TrollHattan, about 50 miles. Here we went on shore, while the steamer ascended a long series of locks to the level of the Wenern Lake at the head of the Falls, the passengers having meanwhile reached the same place by a path on the riverside, thus obtaining a full view of the cascade.

The Wenern Lake is a noble sheet of water, about 90 miles long and 30 miles wide, and this we traversed for its entire length to a village in a pine forest named Hust, where we landed, and procured a vehicle to carry us on to Orebro. It was an oblong box mounted without springs on four wheels, and drawn by two horses, and the road being merely a forest track, was of the roughest, besides which our driver, having before starting fortified himself with a good pint of fiery spirits, drove recklessly; but we reached Orebro at last, and found Count Rosen, with whom and his charming family we spent a few days in making preparations for the works.

From Orebro we resumed our journey by a steamer

along the Malar Lake, by which we were enabled to reach Stockholm, where on arrival one was soon busily employed in securing the services of a sufficient staff of assistants among the military engineers, of whom I soon had thirty, all of whom, with one exception (a Major of Engineers), were either Barons or Counts; but they proved excellent fellows, and performed their duties satisfactorily, in all respects most conscientiously.

Having thus arranged matters as regarded the line from Gothenburg to the capital, it was necessary to inspect the country to the south, and for this examination of 400 miles—scarcely liking to rely on native vehicles—a carriage was purchased, and we determined to post to Malmo, walking over such portions as was necessary.

We thus proceeded to Westeras, where we were entertained to tea and introduced to the Governor by the good and amiable Bishop, continuing our journey next day to Orebro, where I established an office, and commenced work there. Beyond this point, until we were near to Falkoping, we had to make our way on foot, as the road was somewhat remote, but the forest paths were pleasing enough, with secluded lakes, and the abundance of wild strawberries and raspberries growing everywhere about us; but at Falkoping—then a poor-looking place—our progress south seemed likely to meet with serious impediments, for cholera had broken out in some places, and quarantine had been established in all the chief towns through which we had to pass, and the most stringent measures taken to prevent infection.

Our first difficulties were met with on entering the next town, Jonkoping, where we were stopped, and a man put on the box with our driver to conduct us to the Board of flealth, but we told our coachman to drive to the nearest hotel, at which we descended; and having mixed with the people, it seemed to be considered that we had done

all the mischief possible, and that there was no longer any remedy, so we were left in peace.

Jonkoping appeared to be a flourishing place; it is charmingly situated at the southern extremity of Lake Wetter, a sheet of water 84 miles in length, connected both with the North Sea and the Baltic; its chief manufacture then was lucifer matches, for which the surrounding pine forests supplied the material.

Soon after leaving Jonkoping, we skirted the remarkable ferruginous deposits of Taberg, where the ore was being quarried from the face of a clifi, about 300 feet in height, in the midst of the pine woods; and thence for days we saw nothing but pine trees, stopping at night at a post-house, where was but poor accommodation and poorer fare, and where none seemed to welcome us, or regret our departure; but now and then on our way coming across a lovely sylvan lake or retired clearing, with its cluster of humble dwellings, and its wooden chapel and quaint belfry. These surroundings continued the greater part of our way until we reached the University City of Lund, where, on attempting to enter the place, we encountered a guard of soldiers, who stopped our carriage, and detained us for some time until their Commandant arrived, to whom we explained the object of our journey, and who, without any hesitation, mounted into our vehicle and took us to the Governor, and introduced us to him in the kindest manner.

From Lund, the sedate and tranquil, the distance is small to the busy port of Malmo, where we met with the utmost courtesy and kindness from the Governor Troil downwards. Here we stayed for a few days, when letters reached me requiring my presence at Christiana (Norway), and the question arose how to reach that city, for on account of cholera all communication was suspended with the north by steamer, and a journey thither

by land was out of the question, so I consulted with the Governor, who only suggested my hiring a boat, sailing across to Copenhagen, and remunerating the boatmen for their detention in quarantine on their return; but this appeared both costly and difficult, and after a day or so we found a way out of our trouble, inspecting meanwhile the industrious community around us—their harbour (at the entrance to which lay a corvette), its dock, the churches, a large cigar factory (with 3,000 female operatives), and the prison, in which were two murderers awaiting decapitation by the sword, the then mode of execution in Sweden.

At length we prevailed on some fishermen to smuggle us out of the Port at night, and convey us over to Denmark, about nineteen miles away across the Sound, and this we did on a dark and boisterous night in an undecked boat, and were landed at a place called Belle Vue, seven miles from Copenhagen, about 4 a.m., where we were angrily refused admission at a small seaside hotel, but seeing a light in a cottage window near, we found a worthy Dane who undertook to find us a conveyance, which he proceeded to do, leaving us to entertain his wife, who was in bed, until his return, when we soon were on our way to that city of so much interest, Copenhagen. When we arrived we at once went to bed, only very shortly to be disturbed by a visit from the police, demanding our passports, and being destitute of such documents^ were summoned to the police bureau forthwith, where, as we were not without the best of recommendations, we were at once made free of a city fast in the grim clutches of a fatal epidemic, where all places of amusement were closed; where people were actually falling dead in the streets, the pavements of which bore signs of mournings for they were coated with tar as a sanitary measure.

This police privilege of remaining in a city from which

its inhabitants (who were able) were fleeing, we made use of to visit Thorwaldsen's Museum of Sculpture, the Free Kirche, the Royal Palace, and the many notable objects of the place, making many most interesting acquaintances during the visit, as those of Stephens, the translator of ** Frithiot's Saga," and Dr. Hanover, with whom I visited some of the worst cholera-infected localities; and in illustration of the state of things then, I may mention that on visiting an English lady resident, she told us that her coachman had been to receive his orders that forenoon for her afternoon drive, and she just then had been told of his death.

A few days later we heard that a steamer would leave Elsinore for Gothenburg, and we therefore went on thither the day previous to its departure, so as to see the castle, made famous by Shakespeare, and thence the next day went on board the S.S. Hamlet^ northwards, soon encountering her sister, S.S. Ophelia, going south.

Arriving at Gothenburg, found our way barred by quarantine northwards, and had to postpone the journey to Christiana, so resolved to return by the canal to Stockholm, a pleasant voyage of two or three days.

Having provided ample accommodation in the hotel for my numerous assistants, we now proceeded with the preparation of the plans, &c., and having made such arrangements we proceeded by steamer to Gefle, and examined the country thence to Fahlun, on the way to which place we were entertained by some of the members of the Diet to a banquet in a pine wood.

From this inspection we returned to Stockholm, by way of Upsala, the Oxford of Sweden, to which city I had already paid a visit as the guest of the governor, and had become acquainted witl^ many of the professors and the remarkable features of the place, such as the garden of Linnaeus, the huge tumuli of the Scandinavian gods—

Thor, Odin, Frigga, &c., but on this second occasion we were, on account of the cholera, not allowed to alight from our carriage, and at another place we only escaped fumigation by a bribe.

I now made another trip to Gothenburg to meet my wife, who had ventured to come alone from London to stay with me until the completion of my work in Stockholm, where, on returning, we remained, making many friends amongst the kindly Swedes, until the winter began to set in at the end of October, when the plans were completed and put in charge of Major Pringle, the then British Consul, ready for presentation to the Diet.

Among the notable personages this engagement brought me into contact with was the King Barsadotte, the celebrated General of Napoleon I., the only king made by him who retained his crown ; and the good and brave Admiral Sir Edmund Lyons, afterwards Lord Lyons, who I took leave of on his departure to assume the command in the Black Sea in the year following, when he so distinguished himself, by, I believe, silencing the only battery on the sea side of Sevastopol. Count Rosen, the originator of railways in his country, deserves for his kindness my grateful acknowledgments, as do many others eminent then in the capital, who must be yet held in proud remembrance by their compatriots.

At length we took our departure for home by the last steamer leaving Stockholm for Lubeck, the cold becoming intense, and finding the navigation there becoming obstructed by ice. Thence we reached Hamburg, a fine and prosperous city, where, having passed two or three days, we crossed the river Elbe on a ferryboat in an omnibus—with about a dozen Germans, each with his pipe—among floating ice to Harburg, and thence by railway through Hanover to Cologne, where we visited

the cathedral, &c., and went on to Brussels and Paris, home.

It would have been pleasant to have taken part in the execution of these railways, but the Swedish Government decided on executing them, and have since done so, compensating the English syndicate for its outlay on the plans, which I think have been generally adhered to.

AS CHIEF ENGINEER TO THE CHILIAN

GOVERNMENT.

1854 TO 1864.

Railways in Chili and Peru.